Advocate for the Mute | by Aharon Feuerstein

Two principles guided my father, Professor Reuven Feuerstein, in the tremendous therapeutic enterprise he established – a faith in change, and the imperative to grant assistance to every human being. A year after the death of the man who had unwavering faith in the possibility of change. The anniversary of my father’s death approached. The healing processes that previously seemed impossible begin to do their work, the heart somehow adjusts to a world in which there is ..

The anniversary of my father’s death approached. The healing processes that previously seemed impossible begin to do their work, the heart somehow adjusts to a world in which there is no father to hug, and new habits – not to call Father, not to visit him in the evenings, to start the Kiddush prayer without waiting for his voice to fill the room – and insoluble questions are somehow met with answers from unexpected places (the sweet Kiddush prayer recited by my young son, my clever children at the Shabbat table, the singing of Shabbat songs together).

Something inside me softens with the anniversary of his death. The race to say Kaddish (the daily mourner's prayer) is over, but the void my father left brings into sharp focus questions about a man's life and his death, about the presence of a father in the lives of his children even after he is gone. A major question that preoccupied my father all his life preoccupies me as well in his absence – What was his legacy, and what did he charge us with when he passed? One possible answer: To work miracles. And then another question: How does one work miracles?

Caption: He was completely unwilling to resign himself to difficult realities. Professor Reuven Feuerstein at the ceremony to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Cluj in Romania, which took place at Bar Ilan University in 2009. Photograph: Michael Feuerstein

There are No Fateful Decrees

Many of the people who encountered my father and came into his orbit described him as a miracle worker, a magician, one-of-a-kind, a man whose death would leave behind a void that cannot be filled, a crookedness that cannot be made straight. From all corners of the world people flew their families to Israel to meet him so that he could save their children. And my father, in very many of those cases, came through for them. He seemingly miraculously released those who sought his aid from a range of very difficult fates that would have otherwise awaited them. He rallied to help the autistic and the brain-damaged, the mentally incapacitated and those down on their luck -- individuals from a variety of backgrounds with disabilities of various levels of severity. With his unique appearance (a French artist? A rebbe?), and with his undeniable charisma, Father seemed like a professional miracle worker.

My father was very aware of his image, and even if he relished it just a bit he also spent his life fighting it. He sought fiercely to undermine the description of him as a miracle worker. When he wasn’t treating people, he dedicated his time to formulating his therapeutic approach. He took pains to clarify and simplify its principles, to demonstrate their efficacy, to found and sustain an international center that would teach and implement his approach. He cultivated a wide cadre of students and colleagues and took pride in their many capabilities, and unlike a magician he made every effort to lay bare and teach every trick he employed. One of his key phrases was “everyone can do it.” He was referring not just to the malleability of the brain, but also to the notion that “everyone can do it” – can help, save, work miracles. And the fact that everyone can, for him, meant that everyone must.

So how does one work miracles? How do we break through the invisible, obstinate barrier of autism, which by definition is “untreatable”? How do we rehabilitate a person half of whose brain was destroyed in an accident, or in a terror attack, when the doctors insist that “there is nothing to be done”? How do we teach an adult to read after the best teachers and therapists have failed time and again? How do we create a future for people whose genetic syndrome marks their facial appearance as dysfunctional? How do we rehabilitate an emotionally disturbed individual after years of institutionalization “with no hope”? How do we save a child whose parents were persuaded by his medical team to abandon him in the hospital after he was born with a severe birth defect?

Before we delineate the basic principles of the approach, we will recall that Archimedean point, that Reuven Feuerstein point from which, if we lean on it, we can lift up the world. My father spent his life shifting between two different points of emphasis. These two points were, for him, the foundation stone on which the world rested, and the cranny in the rock through which he peered. These two points constituted the source of his tremendous energy, but also determined the line of exacting moral demand that divides the world between those who joined his mission and those had not yet – those whom every effort must be made to bring into the fold.

One point was faith. The faith in a person's ability to change. The faith that there is no decree of fate that cannot be combated. This faith was validated again and again. Children who were dismissed by the educational system as atrocious, as failures, or as merely incorrigible became talented young adults full of potential, and several of them became groundbreaking researchers in their fields. In the most severe cases, such as Rhett's syndrome, my father taught those who turned to him how to connect to their afflicted child, how to instill in him a sense of human warmth, how to relate to him, thereby granting these children a humane fate, drawing them back to their own families and to the family of humanity and thus also granting their parents not just a measure of consolation, but also a radical new meaning to their lives.

Down's syndrome, which was once regarded as grounds for psychiatric institutionalization (remember the scene in Rain Man in which there are Down's syndrome kids, too, in the institution for the autistic?) is today considered—thanks to the struggles of my father and his colleagues—an integral part of our community. Those with Down's syndrome hold down key, useful jobs (my cousin works as an aide in a preschool; my beloved nephew, after finishing his high school exams and volunteering in the army, is now receiving training in various fields in which he'll work in the future). A young student sentenced to a life of occupational therapy by her doctor after a terrible accident (that same student documented in the television program “On Second Glance” [Mabat Sheni]), now works to complete a doctorate, following my father and his colleague's intervention.

He Never Gave In

Indeed my father never stopped having faith. Everyone who came to him became a companion for the journey, a partner in the struggle – a struggle that was at once both human and cosmic. The ability to change was, for my father, one of those axiomatic principles on which the world was based. It was a pre-condition of the laws of nature. This was what enabled my father to challenge the most fundamental laws of biology, on the grounds that "it cannot possibly be so." It cannot possibly be so that the chromosomes have the last word. It cannot possibly be so that the brain cannot be changed.

And so many years before science was forced to admit it was so, my father claimed that the brain could be modified. He was scoffed at by experts who thought that Feuerstein had lost his marbles. But he did not relent. When everyone said that brain cells could only die, my father maintained that the brain could repair itself. Today scientists who work with fMRI can only nod in assent. My father refused to believe that a person's fate was decreed by genetics, and he contended that man has the ability to decide which genes will be expressed. With the advancements in epigenetics, I believe that the day is not far when this prophecy, too, will be verified.

The second point was perhaps the source of inspiration for the first, and the fundamental impetus for his work and his struggles – that wondrous element that enabled him to pry open locked gates, to cleave rocks, to move mountains or, when that wasn't possible, to dig tunnels underneath them – that cranny in the rock from which my father looked out on the image of God and the world of man. This was a sense of imperative. The imperative to help people, all people, with no regard for religion, race, sex, sexual proclivity, religious faith, appearance, financial means, temperament, or social skills. Penniless orphans and far-flung millionaires were assisted by my father, as were both individuals who deeply admired him and those who treated him with outright disrespect.

I remember once when the phone rang at 3am, and my father answered patiently. The next day my mother explained that no, it was not a life-or-death situation. Someone from America had wanted to know how his son was progressing. My father, determined to help the son, did everything in his power so that the estranged father would not take his son back. My father inherited this sense of imperative from his father and mother, pious and charitable residents of Calechima, the slums of the small Romanian city of Botosani. They laid the foundations when they sent out their children after Friday night services to compete in a game of "who can bring more (penniless) guests to the Shabbat table." But the experience that kindled my father's sense of imperative into a steadfast beacon of responsibility was apparently the Holocaust, about which my father said, "We have lost so much, we cannot give up a single child." And for my father, a child meant anyone, of any age, of any background, in any condition.

My father, who was accepting of all people, was completely unable or unwilling to accept diagnoses as decrees of fate. "Don't accept me as I am," he titled one of his books, giving voice to the mute cries of so many children. Don't leave me in this situation, don't abandon me in a haven for idiots, don't be afraid of the frustration I'll feel when I try to integrate. Don't remove me from the human struggle for a better fate. Don't consign me to a future that consists entirely of playing circle games or of staring at a television screen in a calming environment. Don't deny me the pain of those who are fighting in order to fulfill their potential. Don't spare me the fate of humanity. Don't leave me behind.”

He sounded this cry in the ears of those who wanted to hear it, but also in the ears of those who didn't. He was the advocate for the needy, the mute, those who did not know how to join two syllables together. Just as the midrash relates that Jacob crossed back to the other side of the Jordan because he forgot some small vessels there, my father went back for individuals who needed to be returned to the family of man, to the human destiny, to be changed.

This imperative, I should clarify, was not at all mystical for my father. It was expressed as endless creativity. A negative response from an authority figure was, for him, just the starting point for an argument that could end only with the desired response. When these deliberations hit a wall, the honorable professor would put aside his pride and plead, even break down in tears, so as to melt the hardened heart of the sentry blocking the way. "Necessity is the mother of invention," as the adage goes, but when that didn't work, he simply sought a way around it. And so my father instructed parents to move to another city, to a place with a superior placement committee for children with special needs, in order to rescue their child.

The Mediation Innovation

So how does one work miracles?

Faith and imperative dictated for the Feuerstein approach a sea change in our understanding of man. While traditional theories regarded man as a closed box that contained what it contained and lacked what it lacked, for Feuerstein the individual was always an open system. The ability to learn is based on cognitive skills, which could be acquired even by someone who had the bad fortune of not inheriting them "naturally." Although the standard IQ test maintains that someone who cannot compare objects at age five will also not be able to do so at age fifty, the Feuerstein approach shows how to identify the absence of this comparative skill and how to teach a child to acquire and implement it in a range of situations.

The impulsiveness that can make the most talented genius seem like an irredeemable idiot can be identified and treated. It is also possible to teach spatial orientation and memory strategies, the ability to generalize and to gather information. All of these cognitive skills, which until Feuerstein's approach were regarded as integral pars of what was known simply as "intelligence" became instead modular components. If they were absent, they could be acquired; if they were damaged, they could be repaired. They were not employed in some mystical manner but were the necessary and readily-available building blocks to facilitate more effective learning processes.

For many people these cognitive skills are acquired "naturally." Without our even noticing, a child learns what he needs. But when the normal process of acquiring these skills does not work for some reason, then parents, teachers, and, to my father's chagrin, many psychologists regard it as a decree of fate. My father regarded it as an opportunity, an opportunity for the individual to overcome obstacles. The first and foremost tool to employ in fixing or acquiring these skills is the individual. The individual himself.

All of these skills, according to Feuerstein, are acquired by a process of mediation, in which the mediator—a person—situates himself between the learner and reality. Mediation was not Feuerstein's invention. It is the means by which culture (almost every culture) perpetuated itself and developed from generation to generation. This mediation usually takes place naturally, without the mediators knowing that they are doing anything special.

Thus, the father who does not merely reprimand his son for knocking a cup off the table but also teaches him how and why to place it far from the edge is mediating a sense of spatial orientation, planning, and the relationship between cause and effect. The mother who feeds her baby daughter and gazes into her eyes for long periods of time teaches her daughter the ability to focus and not to jump from stimulus to stimulus. The teacher who notices that the class material does to engage the student and finds a way to make the material relevant to the child's world; the mother who modifies her tone so that she will attract her child's attention; and the father who teaches his son a new game in a manner that will challenge but not frustrate him – all are acting as mediators. This process of mediation pays close attention to the learner and to the material being learned, lends meaning to the process, and showcases the learning process to the child and teaches him, with time, how to teach himself.

The process of mediation is rooted in the present, in the moment it takes place, but it is also constantly in dialogue with what lies ahead. The girl who learned to look right and left before crossing the street can learn, if that forward look is mediated for her—to apply those rules of caution to internet surfing as well. The boy who learned from his parents not just to eat for survival but also to incorporate cultural components (napkins, assigned seats, a sequence of courses, and their aesthetic presentation) learns that man does not live by bread alone, and that without culture, aesthetics, and reciprocity, human life is quite meager.

Enemies from Within

My father divided the steadfast enemies of mediation into those from within and those from without. The obstacle within the individual might be any impairment that prevents a person from receiving normal mediation, such as various cognitive syndromes that block or impede mediation. This is the case with countless brilliant children who, because they either absorbed material too quickly or never learned basic problem-solving strategies, suddenly become low-achieving and at times are even referred to special education. In order to break through or bypass these barriers, the mediator has to enlist all of his or her creativity. An impulsive child needs a quieter environment. An insecure child needs a supportive environment. A child on the autistic spectrum needs a mediator who will locate that breach in the solid concrete wall of the spectrum. Such a child surely lacks meaningful cognitive skills, but the strategy my father developed teaches how to identify those impairments and correct them.

But sometimes the obstacle is rooted in the external environment, in the absence of a mediator. My father looked at our brave new world with eyes full of admiration and concern. He admired humanity's path from gathering berries in the ancient wilderness to the invention of the computer, the journey to the moon, development of cardiac catheterization, and the inquiry into the secrets of existence. At the same time, he was terribly concerned about the tendency of more and more parents to neglect the necessary traditional role of parents, that is, to mediate for their children. This essential task is forsaken as parents become busier, grandparents live farther and farther away, and parents sense that their culture is not good enough for their children and that their children (who are so good with computers) seem smarter and more advanced than their parents.

In the never-ending Israeli debate about the dangers of the melting pot, my father fought his whole life for the preservation and cultivation of human cultural diversity around the world, and in Israel in particular. He maintained that a culture that is not passed down from parents to children leads to cultural as well as cognitive gaps, and that children who did not benefit from this mediation did not just fail to learn their culture, but also lacked key cognitive skills.

This, in short, is was what my father stood for. Anyone who wants to learn his approach has a place to do so. Anyone who wants to come and refresh his or her training is also welcome. The simplicity and lucidity of his teachings allow for tremendous complexity. New tools are constantly being developed according to my father's approach, and they are disseminated throughout the world. The International Center for the Enhancement of Learning Potential which is named for him, the Feuerstein Center, directed by my brother Rabbi Rafi Feuerstein, casts my father's light out from Jerusalem like a shining beacon, drawing in children and adults who need his assistance and offering training in many countries worldwide.

We, his students—his many children—look at the world through the eyes of tradition and change. We carry my father's spirit into the next generation, in the hope that this generation will fulfill the potential of the divine image in which it is created and continue to repair God's world.

Also in Blog

Integrating Social Cognition into Therapeutic Practice

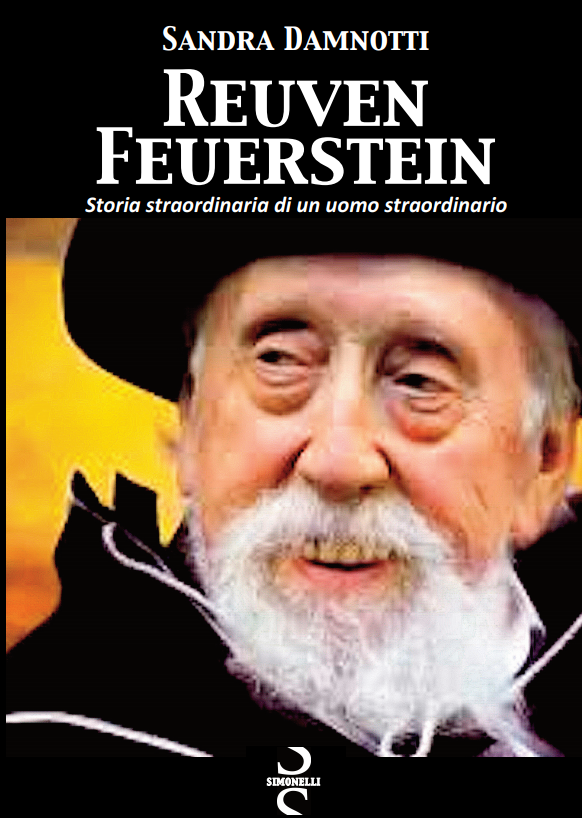

Reuven Feuerstein Storia straordinaria di un uomo straordinario

Reuven Feuerstein Storia straordinaria di un uomo straordinario

Sandra Damnotti tells the extraordinary story of Reuven Feuerstein, the man who taught children in 40 countries how to grow up smart and to adults all over the world he transmitted hope: we can always change, at any age and in any condition. After having recostructing the events that brought him from Bucharest to Jerusalem in the 1940s, the book describes the process of FIE Program’s dissemination in Italy, a country where his method is very popular, and some application experiences in the field of school, vocational training and cognitive rehabilitation.